Belgium

On the defensive

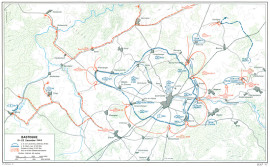

Deployment dates: 19th December – 31st December, 1944.

In late 1944, the Allies – self-assured in their certain victory over Nazi Germany – believed that the war was in its final stages and would soon be over. Germany, weakened on its Western Front by the Normandy and Market Garden Campaigns, had been in full scale retreat from its Eastern Front since the early part of the year. Nazi-German allies such as Japan had suggested that Hitler should sue for peace and the Romanians and Bulgarians had switched sides and joined the Russians. Italy lay defeated.1

Billeted at Camp Mourmelon in France, 101st Airborne were in reserve resting and refitting where they enjoyed light duties and minimal time training. Many paratroopers took passes to Paris whilst others took leave and returned to England.2 Speirs – who had been promoted to the rank of 1st Lieutenant – had also been reassigned from Dog Company to Headquarters Company of the 2nd Battalion, 506th PIR.3

Unbeknownst to the Western Allies, however, Hitler – ensconced in his Wolf’s Lair at Rastenburg in German East Prussia – was briefing his household military staff. According to those who were there, Hitler announced what he termed, a “momentous decision”. He ordered a counterattack out of the Ardennes, with the objective: Antwerp.4

The Ardennes – a densely forested area with rough terrain and rolling hills in south east Belgium – was considered a quiet sector. Assigned to this 75 – 80 mile long front was Major General Troy H Middleton, the US VIII Corps Commander whose infantry divisions – the 28th and 4th – were also resting after intense battle. They had been joined by the 106th – a green and untested division newly arrived from the US. Half of one armoured division – the 9th – was also in reserve.5

In the late afternoon of 16th December, SHAEF headquarters began to receive reports of a German breakthrough in the Ardennes. Eisenhower realised this was a major German offensive and immediately committed his reserve units – which included the 101st Airborne – to the Ardennes.6 However, with so many airborne troopers on passes and off-base, military police were told to find them – and forcibly return any trooper with a screaming eagle patch on his shoulder.7 Less than 18 hours later an entire division of almost 12,000 men was on the move – and Speirs was one of them.8

Formed into regimental combat teams, the 101st left Camp Mourmelon on the afternoon of 18th December (still many troopers short) and were taken to their ‘drop zone’ in trucks.9 Their destination was Werbomont, NorthWest of Bastogne.10

Speirs recalls “the 506th was loaded into large trucks and rushed up to the Bastogne area. I remember we drove all night, with no pee stops – very hard on the bladder. But there was no German aircraft overhead, so we did not get strafed.”11

Travelling to Werbomont by Jeep with his advance party, General McAliffe – acting divisional commander of the 101st Airborne – made a chance decision to stop at Bastogne to confer with Major General Troy H Middleton. Here, revised orders were issued, requiring the 101st to join VIII Corps and defend Bastogne.12

By the end of the day, a circular line of defence – which was permeable and disordered – had been established around Bastogne, and inside this circle the American forces waited. Over the coming days they would endure attacks by as many as fifteen Germany divisions – four of them armoured – supported by heavy artillery.13

The paratroopers now faced by a determined enemy and were forced to battle hard in the bitterly cold weather, without adequate winter clothing.

|

|

“The trees in the Ardennes are planted in rows, so in one direction the visibility was good” wrote Speirs “and in the other direction there was a blank wall of trees.”14

“One of my memories of the Bulge was being in our foxholes with German corpses very close. There had been an attack thru the trees before we arrived and they caught a number of Germans. The bodies were frozen so there was no stench. I turned one over, an artillery forward observer, and found an excellent pair of binoculars around his neck”15 recalled Speirs.

Speirs also remembered “we had a fire fight were a platoon sergeant was killed next to me. I had just knelled down with the sergeant standing next to me when a German machine gun cut loose. It sprayed directly over my head catching the sergeant in the chest. He fell in my arms, but was dead, there was nothing I could do for him. The Germans tried several times to dislodge us from our positions, without success.”16

“One morning” continued Speirs “it was quiet to our front, so I walked forward through the trees. Went about 30 yards, and saw an Alsatian guard dog looking at me. Luckily he did not bark, so I left quietly and quickly. Must have been some troops with him.”17

Another incident during the siege recounted by Speirs was “the story of the Belgian farmer’s cellar. This was somewhere on the outskirts of Bastogne. There was german artillery shelling – close enough to make us look for shelter. It was a stone farmhouse and looked pretty solid. To our surprise when 3 to 4 of us got into the cellar a whole Belgian family was there. They did not seem too alarmed, so we stayed for perhaps an hour or two. With my poor French, the conversation was limited, but there was a lot of smiling and sharing of American candy and rations with the children. I have often wondered what happened to them.18

|

|

It was during this siege of Bastogne, that General McAuliffe – upon receiving an ultimatum from the Germans to surrender – famously replied, ‘Nuts’.

|

|

|

Finally on 26th December, General Patton’s 3rd Army reached Bastogne, effectively ending the siege.19 In the aftermath of this campaign, the 101st Airborne would become known, and would call themselves, the Battered Bastards of Bastogne.

On the offensive

Deployment dates: 1st January – 13th January, 1945.

With the siege of Bastogne effectively ended, military strategy in the Ardennes now changed from the defensive to the offensive.20

The first orders issued to 2nd Battalion were to clear the Bois Jacques woods, situated North of Bastogne between the villages of Foy and Bizory.21 Once accomplished, attention turned to the next objective – the town of Foy.

Easy Company was to lead the attack on Foy, commanded by Lieutenant Dike. The plan was to charge across a 200 metre snow-covered field to reach the village and, using hand grenades, clear the buildings of any Germans.22

Initially the plan seemed to be working as, protected by covering fire, the men of Easy Company moved in a skirmish line across the field. 1st Platoon on the left flank, reached some farm outbuildings, while 2nd and 3rd Platoons continued moving forward. Lieutenant Dike, shielded behind some haystacks, then gave an order which proved to be his downfall. He gestured for 2nd and 3rd platoon to join him behind the haystacks.23 Now that everyone had stopped moving, they were easy targets for the Germans. Company Sergeants converged on the haystack pressing Dike for orders, but, according to accounts made by these men, he stalled and didn’t seem to know what to do. Eventually he came up with a plan. 1st platoon would circle the village to the left from where they would launch their attack.24 Dike would keep the platoon’s mortar and machine gun men at Company HQ behind the haystack were they would direct suppressing fire. But within minutes of leaving the haystacks German snipers began to pick off the eighteen men of 1st platoon.25

Watching the debacle from the edge of the woods was Major Winters – a former commander of Easy company. Screaming orders for the company to move forward and out of harms way, he tried to raise Dike on the radio, to no avail. Just then, he noticed Speirs and ordered him to take over the attack. Speirs’ response was to immediately begin to run across the open field.26

Reaching the haystacks, he relieved Dike and took control. Platoon sergeants, including Sergeant Carwood Lipton, appraised him of the current situation. Carwood Lipton recalls that Speirs then barked out orders to each platoon – giving instructions and direction – before running off with his men right behind him.27

Confident, and buoyed by positive leadership, the troopers began their assault on Foy firing every weapon available and they began to make headway.28 Stranded on the far side of Foy was ‘I’ company – cut off from the rest of the platoon and without a radio – unaware of the unfolding situation around them. Upon learning of their situation, Speirs immediately ran through the village of Foy – a village full of German soldiers and tanks. Eyewitness, Sergeant Carwood Lipton said later, “the Germans were so shocked at seeing an American solider running through their lines – they forgot to shoot!” Once Speirs joined up with ‘I’ company and told them of the current situation – he ran back through the town – once more crossing through the German lines.29 It was a feat of incredible bravery, and one of the actions Speirs is most remembered for today.

“I remember the broad, open fields outside Foy,” Speirs wrote in a 1991 letter, “where any movement brought fire. A German 88 artillery piece was fired at me when I crossed the open area alone. That impressed me.” 30

After the action at Foy, Major Winters recommended Dike be relieved and Speirs be officially put in charge of Easy Company. Colonel Sink agreed.31 Speirs remembers “once in the Ardennes, Colonel Strayer put me in command of E Company. As I recall it was at night when he called me into his tent. I did not know why my predecessor was relieved.”32

Noville

The village of Noville had been the scene of formidable fighting between the Americans and Germans since the start of the Battle of the Bugle. Both sides were fighting for possession of the small hamlet just NorthEast of both Foy and Bastogne.

The US strategy was part of a general offensive aimed at trapping and stopping further German tanks from escaping the area. Colonel Sink ordered 2nd Battalion to lead the attack.33 Speirs, in command of Easy Company (part of 2nd Battalion), would again have to cross open ground and clear a dense wood to get to Noville. The Germans still held the high ground surrounding the town.34 On approach to Noville, Easy Company encountered fire, so Speirs set up a cover of firearms which allowed small groups of men to dash across a small stream.35

By nightfall, Speirs had succeeded in getting his men across the open ground and 2nd Battalion billeted down in hastily dug foxholes waiting for morning, when the attack on Noville would begin. Speirs met with his officers to outline his plan of attack and gave each platoon its orders.36 The attack started at dawn and, despite German resistance and German tanks, by noon 2nd Battalion held Noville. It had been 20th December, 1944 when American soldiers were forced to withdraw from Noville – now, on 15th January, 1945, it was back in American hands.

Rachamps

But there was to be no rest yet. The next day, on orders from General Taylor, Easy company were once more on the attack – this time to clear the village of Rachamps -which lay in a valley to the east of Noville. German resistance quickly crumbled with the Germans fleeing the town. Speirs set up the company Command Post in a convent, whilst the nuns arranged for a local choir to sing for them. Significantly, this marked the first time a Command Post had been housed inside a building since Mourmelon.37 Finally, the following day – after an historic war effort and exhausting winter of intense combat – the 101st Division was ordered off the front line.

Presidential Distinguished Unit Citation

For the first time in the history of the Army an entire division – the 101st Airborne – was awarded the Presidential Distinguished Unit Citation for its performance at Bastogne. This award was presented by General Eisenhower on 15th March, 1945.

- http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-E-Ardennes/USA-E-Ardennes-1.html

- http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/Bastogne/bast-02.htm

- General Order #11 dated 2nd May 1945 PIR

- http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-E-Ardennes/USA-E-Ardennes-1.html. This plan, code-named ‘Wacht am Rhein’ or ‘Watch on the Rhine’ (later renamed Autumn Mist) was designed to secure a crucial victory for the Reich and recapture the port of Antwerp.

- No Silent Night, Barron and Cygan – pages 39-40

- No Silent Night, Barron and Cygan – pages 44

- No Silent Night, Barron and Cygan – pages 48

- No Silent Night, Barron and Cygan – pages 56

- No Silent Night, Barron and Cygan – pages 50

- http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/Bastogne/bast-02.htm

- Letter to Stephen Ambrose from Ronald Speirs dated 29/01/91

- http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/CSI/CSI-Bastogne/MITCHELL.asp.html#IIO

- Band of Brother, Ambrose – iBook edition – page 431

- Letter to Stephen Ambrose from Ronald Speirs dated 29/01/91

- Letter to Stephen Ambrose from Ronald Speirs dated 29/01/91

- Letter to Stephen Ambrose from Ronald Speirs dated 29/01/91

- Letter to Stephen Ambrose from Ronald Speirs dated 29/01/91

- Letter to Stephen Ambrose from Ronald Speirs dated 29/01/91

- http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-the-bulge

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 471/473

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 473

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 496

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 502

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 503

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 504

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 506

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 509

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 511

- Carwood Lipton – Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 510

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 510

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 514

- Letter to Stephen Ambrose from Ronald Speirs dated 29/01/91

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 517

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 519

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 521

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 522

- Band of Brothers, Ambrose – ibook edition – page 533